The music faded away as the radio DJ’s voice flooded into the truck, “That was Eye of the Tiger by Survivor. Still at the top of Canada’s 100 for the fifth week in a row.” Faraidoun turned the truck into the construction yard, and parked. Exiting the truck, he glanced down at his toolbox. Once again, dozens of deep, thick scratches etched through the letters of his name making it impossible to read, erasing him; a hazing tactic used by the other men on the construction site.

A rush of frustration flushed his face. Faraidoun set the tool box on the bed of his truck and peered at the group of men standing together in the construction yard. He opened his tool box and removed a pair of needle nose pliers.

The men were all gathered together and listening to Paul, a confident, wall of a man who was engaging the group in a bit of water cooler gossip about his date the night before. Paul had always given Faraidoun a hard time. He was the primary instigator in what had become a constant battery of discrimination against Faraidoun.

The men were all gathered together and listening to Paul, a confident, wall of a man who was engaging the group in a bit of water cooler gossip about his date the night before. Paul had always given Faraidoun a hard time. He was the primary instigator in what had become a constant battery of discrimination against Faraidoun.

Faraidoun walked up to the group, stopping in front of Paul. Paul stopped mid-story as everyone diverted their attention to Faraidoun.

“What’s up, Frank,” said Paul.

The needle nose pliers worked just like you’d imagine, perfectly pinching Paul’s wide set nostrils in front of the entire group.

“My name is Faraidoun. You should know that considering you’re the one who’s been scratching my name off my tools every damn day. Now, I am going to offer you one more shot at decency and I suggest you take me up on it.”

The welling of frustration and anger Faraidoun was feeling dissipated quickly, being replaced by pride with a touch of guilt. Neither Paul, nor any of Faraidoun’s colleagues at the construction yard ever scratched his name off his tools again.

Get the Gravity newsletter for the latest FAQs, tools, tips and tricks

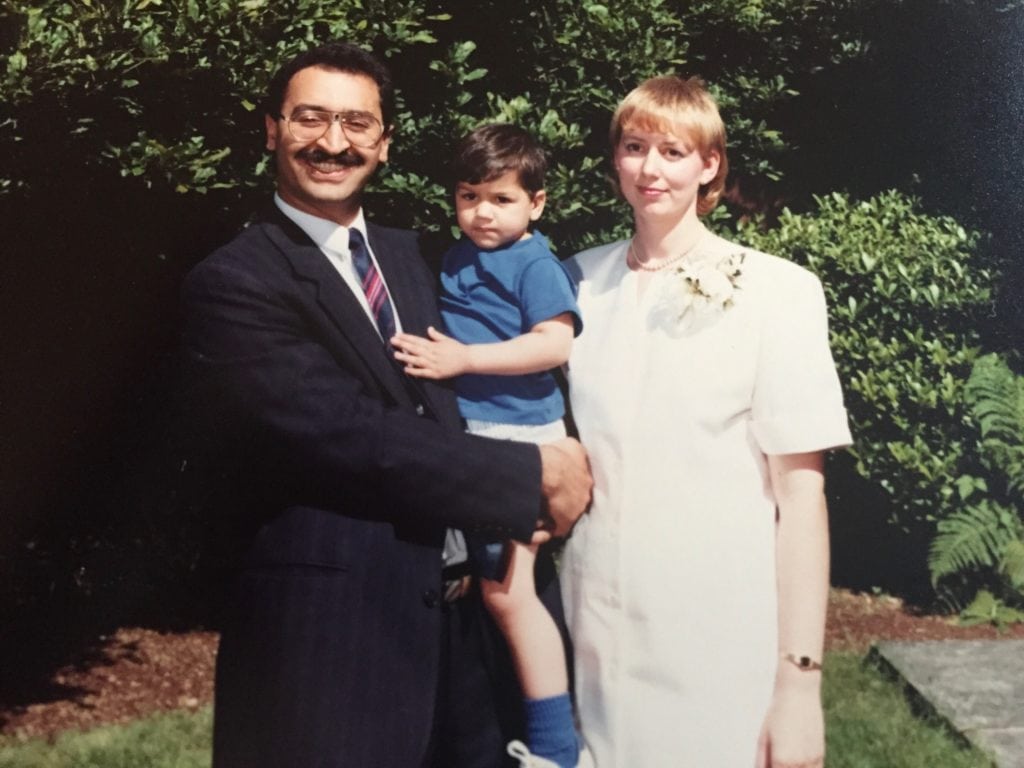

Faraidoun is my father. He was born in Iran and dreamed of coming to the United States at the age of 21, as a refugee fleeing religious persecution. Trouble was, it was 1981 and the Iranians were under an immigration ban because of the Iranian Hostage Crisis. So, instead of coming to America in 1981, he was granted refugee status in Canada.

Though he escaped religious persecution in Iran, he entered a new world of persecution in North America. The anecdote of the construction worker scratching his name off tools is one moment in a daily routine of prejudice and second-classism he suffered as someone who entered a world that is not used to diversity in any sense.

After a while, he left construction and started selling insurance. Today, he is one of the most successful insurance salesmen in Canada, and has been for some time. But, it was a long and hard fought battle to get there, constantly being rejected, in favor of a white person, to represent clients.

Of course, overt racism is the easiest thing to point out. It is the little things and, at the time, seemingly insignificant events that when amplified to an entire people result in a massive problem. People are uncomfortable with what they don’t know. Even as children, we are trained to distrust that which we don’t know. Think of  “stranger danger”: if you are taught as a child that anyone unfamiliar to you is a dangerous person, what are you going to think when you meet someone who looks or speaks differently than you?

“stranger danger”: if you are taught as a child that anyone unfamiliar to you is a dangerous person, what are you going to think when you meet someone who looks or speaks differently than you?

When I was born, my parents decided to make my first name Phillip. This was in response of my parents being afraid of assumed racism and prejudice against me. However, to my friends and my family, I am Naveed, which is my middle name. There are only two cases where I am not Naveed – at work, where I am Phillip, and to my daughter, where I am Baba.

I work in sales, speaking with business owners about their credit card processing entirely through the phone. I go by Phillip at work, because, just like my father, I find that people might feel uncomfortable dealing with someone named Naveed. They might not trust me as much as they would someone named Philip. They might think they aren’t talking to an American, rather to someone overseas. Though they are partially right; I was born in Canada, but have a dual citizenship. Regardless, there is a laundry list of issues, because whether we know it or not, we have developed subconscious bias in our societies.

For example, growing up as a child in Canada most of my friends were white. My mother is American and white. My father is a Persian from Iran. While playing, my friends or classmates would ask me, “Naveed, what are you?” To which my answer was always, “I’m half Persian and half normal.”

No one told me to say normal. I could have said American or white, but it was a societally defined segregation between the normal and the “not normal” that influenced me, even as a young child. As I’ve come to learn, the truth of the matter is that there is no such thing as normal.

Today, I live in Seattle. It’s a progressive city that doesn’t put a premium on normalcy. The city and its inhabitants not only celebrate people of different cultures and beliefs, but encourage and protect it. Instead of being afraid of the unknown, we yearn to discover more of it.

But, before coming here, I traveled all over the world where I learned from unique cultures who helped open my eyes and shape who I am today. Along the way, I haven’t lost any of my traditions. I didn’t become less American, less Persian, less me. There’s no way I could have, because at the end of the day I am a person. And so is everyone else.

The divisions we create in society are based on fear, the unknown, and the unfamiliar.

But, it’s mostly the fear that drives us – fear of change, fear of having to learn other people’s cultures and opinions. People don’t want to muddy up their lives. They want Netflix, comfort, simplicity, familiarity. Trouble is, the more we isolate ourselves from each other, the harder it will be for humanity to progress in a meaningful manner.

The world has come a long way since my father immigrated to Canada in 1981. It has come a long way since I was named Phillip. And now having recently become a father myself, I don’t take much solace as the world begins to move to the old ways of division and exclusiveness. I think the best thing we can all do is to get to know your neighbors, talk to someone who thinks differently than you, or take a walk in someone else’s shoes. It’d be a shame if we didn’t resist moving backwards, when our country has made so many leaps ahead.

Phil is on the Merchant Relations team at Gravity Payments. For more on diversity at Gravity, check out our “Embracing Diversity” series.